Kaze to Ki No Uta Read Online Volume 12

| Kaze to Ki no Uta | |

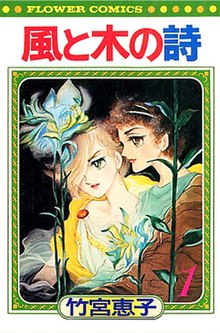

The cover of the first tankōbon book, featuring Gilbert (left) and Serge (right) | |

| 風と木の詩 | |

|---|---|

| Genre | Shōnen-ai |

| Created past | Keiko Takemiya |

| Manga | |

| Written by | Keiko Takemiya |

| Published by | Shogakukan |

| Mag |

|

| Demographic | Shōjo |

| Original run | Feb 29, 1976 – June 1984 |

| Volumes | 17 |

| Original video animation | |

| Kaze to Ki no Uta Sanctus: Sei Naru Kana | |

| Directed by | Yoshikazu Yasuhiko |

| Studio | Triangle Staff |

| Released | Nov 6, 1987 |

| Runtime | 60 minutes |

Kaze to Ki no Uta (Japanese: 風と木の詩, lit. "The Verse form of Air current and Trees" or "The Song of Wind and Trees") is a Japanese manga series written and illustrated by Keiko Takemiya. It was serialized in the manga magazine Shūkan Shōjo Comic from 1976 to 1980, and in the manga magazine Petit Bloom from 1981 to 1984. I of the earliest works in the shōnen-ai (male person–male person romance) genre, Kaze to Ki no Uta follows the tragic romance between Gilbert Cocteau and Serge Battour, two students at an all-boys boarding school in belatedly 19th century France.

The series was developed and published amid a meaning transitional period for shōjo manga (manga for girls), as the medium shifted from an audience composed primarily of children to an audition of adolescents and immature adults. This shift was characterized by the emergence of more narratively circuitous stories focused on politics, psychology, and sexuality, and came to exist embodied by a new generation of shōjo manga artists collectively referred to as the Year 24 Group, of which Takemiya was a member. The mature subject area material of Kaze to Ki no Uta and its focus on themes of sadomasochism, incest, and rape were controversial for shōjo manga of the 1970s; it took 7 years from Takemiya'southward initial conceptualization of the story for her editors at the publishing company Shogakukan to agree to publish it.

Upon its eventual release, Kaze to Ki no Uta achieved significant critical and commercial success, with Takemiya winning the 1979 Shogakukan Manga Honor in both the shōjo and shōnen (manga for boys) categories for Kaze to Ki no Uta and Toward the Terra, respectively. It is regarded as a pioneering work of shōnen-ai, and is credited with widely popularizing the genre. An anime moving-picture show adaptation of the series, Kaze to Ki no Uta Sanctus: Sei Naru Kana ( 風と木の詩 SANCTUS-聖なるかな- , lit."The Poem of Wind and Trees Sanctus: Is It Holy?"), was released as an original video animation (home video) in 1987.

Synopsis [edit]

The city of Arles in France, where the series is set

The serial is set in late 19th century France, primarily at the fictional Lacombrade Academy, an all-boys boarding school located on the outskirts of the city of Arles in Provence.

Serge Battour, the teenaged son of a French viscount and a Roma adult female, is sent to Lacombrade at the request of his tardily father. He is roomed with Gilbert Cocteau, a misanthropic student who is ostracized by the schoolhouse'due south pupils and professors for his truancy and sexual relations with older male person students. Serge'south efforts to befriend his roommate, and Gilbert'south efforts to simultaneously drive away and seduce Serge, form a complicated and disruptive relationship between the pair.

Gilbert'south apparent cruelty and promiscuity are the result of a lifetime of neglect and abuse, as perpetrated chiefly by his uncle Auguste Fellow. Auguste is a respected figure in French loftier social club who has physically, emotionally, and sexually driveling Gilbert since he was a kid. His manipulation of Gilbert is then meaning that Gilbert believes that the ii are in dearest, and he remains beguiled by Auguste even after he later learns that Auguste is non his uncle, but his biological begetter.

Despite threats of ostracism and violence, Serge perseveres in his attempts to bond with Gilbert, and the two eventually become friends and lovers. Faced with rejection by the faculty and students of Lacombrade, Gilbert and Serge flee to Paris and live for a curt while as paupers. Gilbert is unable to escape the trauma of his by, and descends into a life of drug use and prostitution. While hallucinating nether the influence of opium, he runs in front of a moving wagon and dies under its wheels, convinced that he has seen Auguste. Some of the pair'south friends, who have recently rediscovered the couple, find and console the traumatized Serge.

Characters [edit]

Voice actors in Kaze to Ki no Uta Sanctus: Sei Naru Kana are noted where applicable.[1]

Main characters [edit]

- Gilbert Cocteau ( ジルベール・コクトー , Jirubēru Kokutō )

- Voiced by: Yūko Sasaki

- A fourteen-yr-quondam student at Lacombrade from an aristocratic family unit in Marseille. He is the illegitimate kid of his mother Anne Marie and her brother-in-law Auguste Swain, the latter of whom has driveling Gilbert physically, emotionally, and sexually since he was a child. This abuse has left Gilbert equally an hating cynic, unable to express love or affection except through sex. Gilbert is initially antagonistic and violent towards his new roommate Serge, and rejects Serge's early attempts to befriend him. Serge's persistent altruism slowly wins Gilbert over, and the two abscond to Paris as lovers. Gilbert has difficulty adjusting to their new lives of genteel poverty and begins using drugs and engaging in prostitution, and dies subsequently beingness struck by a wagon while under the influence of opium.

- Serge Battour ( セルジュ・バトゥール , Seruju Batūru )

- Voiced past: Noriko Ohara

- A fourteen-year-old student at Lacombrade, and heir to an aristocratic firm. The orphaned son of a French viscount and a Roma woman who faces bigotry for his mixed ethnicity, Serge is a musical prodigy with a noble and humanistic sense of morality. Despite Gilbert's initial ill treatment of him, he remains devoted in his attempts to help and sympathize him. His attraction to Gilbert causes him confusion and distress, particularly when he finds that he can depend on neither the church nor his friends for guidance and support. He gradually grows closer to Gilbert every bit friends and afterward lovers, and the ii flee Lacombrade together.

Secondary characters [edit]

- Auguste Beau ( オーギュスト・ボウ , Ōgyusuto Bō )

- Voiced past: Kaneto Shiozawa

- Gilbert's legal uncle, later revealed to be his biological father. Adopted into the house of Cocteau as a child, Auguste was raped past his elderberry step-blood brother in his own youth and came to abuse Gilbert from a young historic period. At beginning attempting to heighten Gilbert to be an "obedient pet", he later works to transform him into a "pure" and "artistic" individual through neglect and manipulation of Gilbert's obsessive dear for him. Upon learning of Serge'southward relationship with Gilbert, he works to separate the pair.

- Pascal Biquet ( パスカル・ビケ , Pasukaru Cycle )

- Voiced past: Hiroshi Takemura

- An eccentric, iconoclastic classmate of Serge and Gilbert and a close friend of the erstwhile. A super senior who is dismissive of religion and classical educational activity, he insists upon the importance of science and takes it upon himself to teach Serge about sexuality. While mildly attracted to Gilbert, he is the about frankly heterosexual of Serge'southward confidants, and helps to introduce Serge to women.

- Karl Meiser ( カール・マイセ , Kāru Maise )

- Voiced by: Tsutomu Kashiwakura

- Serge'due south first friend at Lacombrade. A gentle, pious male child who struggles with his attraction to Gilbert.

- Arion Rosemarine ( アリオーナ・ロスマリネ , Ariōn Rosumarine )

- Voiced past: Yoshiko Sakakibara

- The sadistic student superintendent at Lacombrade, nicknamed the "White Prince". A afar relative of the Cocteau family, he was raped by Auguste at the historic period of 15. Rosemarine cooperates with Auguste's manipulation of Gilbert, but forms a friendship with Serge and ultimately aids Gilbert and Serge in their escape to Paris.

- Jules de Ferrier ( ジュール・ド・フェリィ , Jūru exercise Feryi )

- A student supervisor at Lacombrade, and Rosemarine's childhood friend. His aristocratic family's fortune was lost with the death of his father, and he is merely able to nourish Lacombrade through his intelligence and friendship with Rosemarine. He provides condolement and guidance to Gilbert and Rosemarine through their various troubles.

Development [edit]

Context [edit]

Keiko Takemiya fabricated her debut as a manga creative person in 1967, and while her early works attracted the attention of manga magazine editors, none achieved any particular critical or commercial success.[iii] Her debut occurred in the context of a restrictive shōjo manga (girls' manga) publishing civilization: stories were marketed to an audience of children, were focused on uncomplicated subject material such as familial drama or romantic comedy,[iv] and favored Cinderella-like female protagonists defined by their passivity.[5] [6] Beginning in the 1970s, a new generation of shōjo artists emerged who created manga stories that were more psychologically complex, dealt directly with topics of politics and sexuality, and which were aimed at an audition of teenage readers.[7] This grouping of artists, of which Takemiya was a member, came to be collectively referred to as the Year 24 Group.[a] The group contributed significantly to the development of shōjo manga by expanding the genre to contain elements of science fiction, historical fiction, take chances fiction, and aforementioned-sex romance: both male person–male (shōnen-ai and yaoi) and female-female person (yuri).[9]

In the December 1970 result of Bessatsu Shōjo Comic, Takemiya published a ane-shot (standalone unmarried chapter) male person–male romance manga titled Yuki to Hoshi to Tenshi to... ( 雪と星と天使と… , "Snow and Stars and Angels and...").[three] [10] That story, subsequently re-published under the title Sanrūmu Nite ( サンルームにて , "In the Sunroom"), was the showtime work in the genre that would go known as shōnen-ai [11] and granted Takemiya greater critical recognition.[12]

From 1971 to 1973, Takemiya and fellow Year 24 Grouping member Moto Hagio shared a rented house in Ōizumigakuenchō, Nerima, Tokyo nicknamed the "Ōizumi Salon", which served as an important gathering point for Year 24 Group members and their affiliates.[2] Their side by side-door neighbor and friend Norie Masuyama came to be a significant influence on both artists; though Masuyama was non a manga artist, she was a shōjo manga enthusiast motivated by a want to elevate the genre from its condition as a frivolous distraction for children to a serious literary art form, and introduced Takemiya and Hagio to literature, magazines, and films that came to significantly inspire their works.[ii] [13]

Of the works Masuyama introduced to Takemiya, novels by writer Herman Hesse in the Bildungsroman genre were particularly relevant to the development of Kaze to Ki no Uta.[14] Masuyama introduced Takemiya and Hagio to Beneath the Wheel (1906), Demian (1919), and Narcissus and Goldmund (1932);[thirteen] Demian was particularly impactful on both artists, straight influencing the plot and setting of both Takemiya'southward Kaze to Ki no Uta and Hagio'southward own major contribution to the shōnen-ai genre, The Heart of Thomas (1974).[fourteen] While none of Hesse'south stories are explicitly homoerotic, they inspired the artists through their depictions of potent bonds between male characters, their boarding school settings, and their focus on the internal psychology of their male protagonists.[15] Other works that informed the development of Kaze to Ki no Uta were the European drama films if.... (1968), Satyricon (1969), and Death in Venice (1971), which screened in Japan in the 1970s and influenced both Takemiya and Hagio in their depiction of "preternaturally beautiful" male person characters;[2] Taruho Inagaki'due south The Aesthetics of Boy Dearest (1970), which influenced Takemiya to select a school every bit the setting for her series;[16] and issues of Barazoku, the offset commercially-circulated Japanese gay men's magazine.[17] [b]

Production [edit]

While Takemiya began developing the story of Kaze to Ki no Uta in the years immediately preceding her professional debut, she faced 2 obstacles in publishing the story: her inability to illustrate the story because she did not possess sufficient knowledge of its European setting,[18] and a depression level of editorial freedom and autonomy that was bereft to publish a series equally radical equally Kaze to Ki no Uta.[19] To learn more about the subject field of the serial, Takemiya travelled to Europe with Hagio, Masuyama, and Year 24 Group fellow member Ryoko Yamagishi.[20] [c] She stated that the trip made her "more concerned with details. After I knew how to make a stone-paved street, I as well watched repairs on it and stared at the blocks which were used."[20] Takemiya connected to visit Europe annually, staying in unlike countries for a period of ane month.[21] [22]

To address her lack of editorial freedom, Takemiya sought to build her profile as an artist by creating a manga series that would have mass appeal.[xix] That series, Pharaoh no Haka (ファラオの墓, The Pharaoh's Tomb, 1974–1976), follows the kishu ryūritan ("noble wandering narrative") story formula of an exiled king who returns to pb his kingdom to greatness, which Takemiya chose specifically because it was pop in manga at the fourth dimension.[19] The series succeeded at boosting Takemiya's popularity equally an artist, peculiarly among female person readers, and granted her the necessary influence at her publisher Shogakukan to be able to publish Kaze to Ki no Uta.[22] [23] In all, it took nearly seven years for Takemiya to, in her words, "earn the correct"[24] to publish the series.[25]

In developing main characters of the series, Takemiya stated that Gilbert's complex background necessitated an every bit compelling groundwork for Serge, and thus decided to focus on Serge'southward parents. She drew inspiration for Serge's mixed ethnic background from La Dame aux Camélias (1852), saying "if you lot had to tell a story almost a child of a viscount, I idea, y'all had no other choice only La Matriarch aux Camélias."[21] At the time, censorship codes specifically forbade depictions of male person-female sex in manga, but ostensibly permitted depictions of male person–male sex.[12] [23] The focus on male person protagonists over female protagonists – still a relatively new practice in shōjo manga at the time – allowed Takemiya to write a sexually explicit story that she believed would appeal to female readers,[26] stating that "if there is a sex scene betwixt a boy and a girl, [readers] don't like it because information technology seems too existent. Information technology leads to topics like getting pregnant or getting married, and that'southward too real. But if it's two boys, they can avoid that and concentrate on the beloved aspect."[26]

Release [edit]

Kaze to Ki no Uta began serialization in Shūkan Shōjo Comic on Feb 29, 1976.[27] [28] The series attracted controversy for its sexual depictions: the first chapter opens with a male–male person sex scene,[sixteen] and ofttimes portrays violent sexual acts such as sadomachosicm, incest, and rape.[27] [29] Takemiya has stated that she was concerned how parent-teacher associations would react to the series, equally Shūkan Shōjo Comic publisher Shogakukan was a "stricter" company all-time known for publishing academic magazines for schoolchildren.[25] Reader letters in Shūkan Shōjo Comic were divided between those who were offended by the subject field textile of the series, and those who praised its narrative complexity and explicit representations of sexual activity.[10] [thirty]

In 1980, Shūkan Shōjo Comic editor Junya Yamamoto became the founding editor of Petit Flower, a new manga magazine aimed at an audience of adult women that published titles with mature subject material.[31] Kaze to Ki no Uta moved to the new mag, and the concluding affiliate of the series published in Shūkan Shōjo Comic was released on November 5, 1980. Serialization continued in Petit Flower beginning in the Feb 1981 event, where it continued until the conclusion of the series in the June 1984 issue.[27] [32] The series, which was significantly longer than Takemiya's previous works,[10] was collected equally seventeen tankōbon volumes published under Shogakukan's Flower Comics imprint.[22] The series was translated and published outside of Japan for the start time in 2018, by Spanish-linguistic communication publisher Milky Way Ediciones.[33]

Themes and analysis [edit]

Gender [edit]

The chief characters of Kaze to Ki no Uta are bishōnen (lit. "beautiful boys"), a term for androgynous male characters that sociologist Chizuko Ueno describes as representing "the idealized self-image of girls".[34] Takemiya has stated that her use of protagonists that blur gender distinctions was washed intentionally, in gild "to mentally liberate girls from the sexual restrictions imposed on united states of america [as women]."[35] Past portraying male characters with concrete traits typical of female characters in manga – such every bit slender bodies, long pilus, and large optics – the presumed female reader is invited to self-identify with the male protagonist.[34]

This self-identification among girls and women assumes many forms; art critic Midori Matsui considers how this representation appeals to adolescent female readers by harking back to a sexually undifferentiated state of childhood, while also allowing them to vicariously contemplate the sexual attractiveness of boys.[5] James Welker notes in his field work that members of Nippon's lesbian community reported being influenced past manga featuring characters who blur gender distinctions, specifically citing Kaze to Ki no Uta and The Rose of Versailles by Year 24 Group member Riyoko Ikeda.[36] This self-identification is expressed in negative terms past psychologist Watanabe Tsueno who sees shōjo manga as a "narcissistic space" in which bishōnen operate simultaneously as "the perfect object of [the readers'] want to love and their desire for identification", seeing Kaze to Ki no Uta equally the "apex" of this tendency.[37]

Manga scholar Yukari Fujimoto argues that female interest in shōnen-ai is "rooted in hatred of women", which she argues "sounds as a base note" throughout the genre in the form of misogynistic thoughts and statements expressed by male characters in the genre.[38] She cites as testify Gilbert's overt cloy towards women, arguing that his misogynistic statements serve to describe the reader's attending to the subordinate position women occupy in order; as the female reader is ostensibly meant to self-identify with Gilbert, these statements expose "the mechanisms past which women cannot help falling into a state of self-hatred".[39] To Fujimoto, this willingness to "[plow] around" these misogynistic statements against the reader, thus forcing them to examine their ain internalized sexism, represents "one of the keys" to understanding the influence and legacy of Kaze to Ki no Uta and works like it.[40]

Sex activity and sexual violence [edit]

I wanted to tell women what sex was without veiling it, including bad things as well equally good things. Drawing sex as an important theme in relation to propriety seems naturally acceptable. But sex involves an event of power. From the old days, during war, men used to rape women of an enemy land. In order to empathise such circumstances surrounding women, in these peaceful days, women should recollect straight about sexual practice without fear, not just about sex with fearfulness. I thought that the about important issue for women was sex. So, I tried to imagine how I could convey the message directly to women.

—Keiko Takemiya[25]

Shōnen-ai allowed shōjo manga artists to depict sex activity, which had long been considered taboo in the medium.[41] There has been significant bookish focus on the motivations of Japanese women who read and created shōnen-ai in the 1970s,[42] with manga scholar Deborah Shamoon because how shōnen-ai permitted the exploration of sexual practice and eroticism in a mode that was "distanced from the girl readers' own bodies", equally male–male sex is removed from female concerns of wedlock and pregnancy.[11] Yukari Fujimoto notes how sex scenes in Kaze to Ki no Uta are rendered with "an unprecedented boldness," depicting "sexual want as overwhelming power."[41] She examines how the abuse suffered by Gilbert has rendered him every bit "a creature who cannot be without sexual beloved" who thus suffers "the pain of passivity". By applying passivity, a trait that is stereotypically associated with women, to male characters, she argues that Takemiya is able to depict sexual violence "in a purified form and in a way that protects the reader from its raw pain".[43] While these scenes of sexual violence "would be all too realistic if a woman were portrayed as the victim", past portraying the field of study as a homo, "women are freed from the position of always being the 1 'done to,' and are able to take on the viewpoint of the 'doer,' and also the viewpoint of the 'looker.'"[44]

Midori Matsui similarly argues Gilbert exists equally a "pure object of the male person gaze", an "effeminate and cute boy whose presence solitary provokes the sado-machochistic desire of older males to rape, humiliate, and care for him as a sexual commodity".[45] In this sense, she argues that Gilbert represents a parody of the femme fatale, while at the aforementioned fourth dimension "his sexuality evokes the destructive chemical element of beggary."[46] Like Fujimoto, she concurs that the sexual corruption of Gilbert "functions to arouse readers' fears concerning their own sexuality", but equally these acts occur to a male grapheme, "information technology distances girls from their own violation within patriarchy" and lets them "gain the 'gaze' with which they can reduce the male trunk to the object of their desire".[45] Thus, Gilbert is a contradiction betwixt the "feminine power of seduction that usurps the rationality of the masculine subject" while also reinforcing "conventional metaphors of feminine sexuality equally a dark seducer".[46]

Kazuko Suzuki considers that while guild oft shuns and looks down upon women who are raped in reality, shōnen-ai depicts male person characters who are raped as however "imbued with innocence" and typically however loved by their rapists after the act.[47] She cites Kaze to Ki no Uta as the primary work that gave rise to this trope in shōnen-ai manga, noting how the narrative suggests that individuals who are "honest to themselves" and love only one other person monogamously are regarded every bit "innocent". That is, so long as the protagonists of shōnen-ai "go along to pursue their supreme honey within an ideal homo human relationship, they can forever retain their virginity at the symbolic level, despite having repeated sex in the fictional world."[48]

Occidentalism [edit]

The French setting of Kaze to Ki no Uta is reflective of Takemiya's own involvement in European culture,[18] as reflective of a generalized fascination with Europe in Japanese girls' culture of the 1970s.[49] Takemiya has stated that interest in Europe was a "characteristic of the times," noting that gravure fashion magazines for girls such as An An and Non-no often included European topics in their editorial coverage.[50] She sees the fascination as stemming in part from sensitivities around depicting non-Japanese settings in manga in the aftermath of the Second World War, stating that "you lot could describe anything about America and Europe, but not so, about 'Asia' every bit seen in Japan."[51]

Manga scholar Rebecca Suter notes how the recurrence of Christian themes and imagery throughout the series – crucifixes, Bibles, churches, Madonnas and angels appear both in the diegesis and as symbolic representations in non-narrative artwork – tin can be seen every bit a sort of Occidentalism.[52] Per Suter, Christianity'southward disapproval of homosexuality appears in Kaze to Ki no Uta equally "one of many obstacles to the realization of the beloved between [Gilbert and Serge], a means to complicate the plot and prolong the titillation for the reader." At the same time, the series' appropriation of western religious symbols and attitudes for creative purposes "parallels and subverts a key aspect of Orientalism – namely, the romanticisation of Asia as inherently more than spiritual than the West, and its simultaneous stigmatisation as superstitious and backward."[52]

Works by the Year 24 Group often used western literary tropes, especially those associated with the Bildungsroman genre, to stage what Midori Matsui describes as "a psychodrama of the boyish ego".[5] Takemiya has expressed ambivalence about that genre characterization being practical to Kaze to Ki no Uta; when artist Shūji Terayama described the series as a Bildungsroman, Takemiya responded that she "did not pay attention to such classification" when writing the series, and that when she heard Terayama's comments she "wondered what Bildungsroman was", remarking that she "did non know literary categories."[18] In this regard, several commentators have assorted Kaze to Ki no Uta to Moto Hagio's The Heart of Thomas through their shared inspirations from the Bildungsroman novels of Herman Hesse (meet Context to a higher place). Both Kaze and Thomas follow like narrative trajectories, focusing on a tragic romance between boys in a European setting, and where the death of one boy figures heavily into the plot.[10] Kaze to Ki no Uta is significantly more sexually explicit than both The Middle of Thomas and Hesse's novels,[sixteen] with anime and manga scholar Minori Ishida noting that "Takemiya in item draws on latent romance and eroticism between some male characters in Hesse'due south writing".[53] Midori Matsui considers Kaze to Ki no Uta as "ostensibly a Bildungsroman" that is "hugger-mugger pornography for girls [...] boldly correspond[ing] boys driven past sexual want and engaged in intercourse", equally contrasting the largely non-sexual Centre of Thomas.[45]

Reception and legacy [edit]

In 1979, Takemiya won the Shogakukan Manga Honour in both the shōjo and shōnen (manga for boys) categories for Kaze to Ki no Uta and Toward the Terra, respectively.[54] Roughly 4.ix million copies of collected volumes of Kaze to Ki no Uta are in print.[55]

Kaze to Ki no Uta has been described as a "masterpiece" of shōnen-ai, and is credited with widely popularizing the genre.[29] [56] Yukari Fujimoto notes that Kaze to Ki no Uta (forth with The Heart of Thomas and Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi) made male homosexuality part of "the everyday landscape of shōjo manga" and "ane of its essential elements",[38] while manga scholar Kazuko Suzuki notes Kaze to Ki no Uta as "1 of the first attempts to depict true boding or ideal relationships through pure male person homosexual love".[29] James Welker concurs that Kaze to Ki no Uta and The Heart of Thomas "almost certainly helped foster increasingly diverse male person–male romance narratives within the broader shōjo manga genre from the mid-1970s onward".[57]

Although some Japanese critics dismissed Kaze to Ki no Uta as a "second rate false"[58] of The Center of Thomas, information technology was ultimately Kaze to Ki no Uta that had the more significant long-term impact on male person-male romance manga through its depictions of explicit sexual relations between characters.[58] Previously, sex activity in shōjo manga was confined nearly exclusively to doujinshi (self-published manga);[56] the popularity of Kaze to Ki no Uta prompted a boom in the production of commercially published shōnen-ai beginning in the tardily 1970s, and the development of a more robust yaoi doujinshi subculture.[3] [58] This trend towards sexual practice-focused narratives in male–male person romance manga accelerated with founding of the manga magazine June in 1978, of which Takemiya was an editor and major contributor. June was the first major manga mag to publish shōnen-ai and yaoi exclusively, and is credited with launching the careers of dozens of yaoi manga artists.[29] [34]

Kaze to Ki no Uta has been invoked in public debates on sexual expression in manga, particularly debates on the ethics and legality of manga depicting minors in sexual scenarios. In 2010, a revision to the Tokyo Metropolitan Ordinance Regarding the Healthy Development of Youths was introduced that would have restricted sexual depictions of characters in published media who appeared to be minors, a proposal that was criticized by multiple anime and manga professionals for unduly targeting their industry.[59] Takemiya wrote an editorial critical of the proposal in the May 2010 issue of Tsukuru, arguing that it was "ironic" that Kaze to Ki no Uta, a series that "many of today's mothers had grown upwards reading, was at present in danger of being banned as 'harmful' to their children."[60] In an interview with the BBC, Takemiya responded to the charge that depictions of rape in Kaze to Ki no Uta condone the sexualization of minors by stating that "such things do happen in real life. Hiding information technology will non arrive become away. And I tried to portray the resilience of these boys, how they managed to survive and regain their lives after experiencing violence."[24]

[edit]

An anime film accommodation, Kaze to Ki no Uta Sanctus: Sei Naru Kana, was released equally an original video animation (OVA) on November 6, 1987. The film was produced past Triangle Staff, and directed by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko with Sachiko Kamimura as animation manager.[32] [61] The film's soundtrack was released by Pony Coulee in 1987.[32]

A radio drama adapting the first volume of Kaze to Ki no Uta aired on TBS Radio, with Mann Izawa as scriptwriter and Hiromi Become equally the voice of Gilbert.[32] The series has been adjusted for the phase several times: by the theater visitor April Firm in May 1979, with Efu Wakagi as Gilbert and Shu Nakagawa as Serge;[32] and in the early 1980s past an all-female troupe modelled off of the Takarazuka Revue.[62]

Two Kaze to Ki no Uta image albums take been released by Japan Columbia: the cocky-titled Kaze to Ki no Uta in 1980, and Kaze to Ki no Uta: Gilbert no Requiem ( ジルベールのレクイエム , "The Poem of Wind and Copse: Gilbert's Requiem") in 1984. Kaze to Ki no Uta: Shinsesaizā Fantajī ( 風と木の詩 シンセサイザー・ファンタジー , "The Verse form of Current of air and Trees: Synthesizer Fantasy"), a remix album of the 1980 cocky-titled prototype album, was released in 1985.[32] In 1983, Shogakukan published Le Poèm du Vent et des Arbres, an artist's book featuring original illustrations by Takemiya of characters from Kaze to Ki no Uta.[32]

Kami no Kohitsuji ( 神の子羊 , "The Lamb of God"), a 3-novel sequel to Kaze to Ki no Uta, was published past Kofusha Publishing from 1992 to 1994. The novels were written by Norie Masuyama, under the pen name Norisu Haze. Takemiya illustrated the cover of each novel[32] but otherwise had no artistic involvement in Kami no Kohitsuji, instead granting permission to Masuyama to write a continuation of the manga serial.[63]

Notes [edit]

- ^ The grouping was then named because its members were born in or around year 24 of the Shōwa era (or 1949 in the Gregorian calendar).[eight]

- ^ Hagio has reported that she was uninterested in the sexually-explicit Barazoku, but that the magazine especially affected Takemiya and Masuyama.[17]

- ^ None could speak French, so the grouping communicated with locals using drawings; Takemiya reports that "at an data desk of a hotel, I explained that we needed a room with a bathtub and shower, cartoon illustrations."[xx]

References [edit]

- ^ Yasuhiko, Yoshikazu (director) (November 6, 1987). と木の詩 SANCTUS-聖なるかな- [The Poem of Wind and Trees Sanctus: Is It Holy?] (Motion pic). Japan: Triangle Staff.

- ^ a b c d Azusa 2021, p. 80.

- ^ a b c Welker 2015, p. 47.

- ^ Thorn 2010, p. V.

- ^ a b c Matsui 1993, p. 178.

- ^ Suzuki 1999, p. 246.

- ^ Shamoon 2012, p. 102.

- ^ Hemmann 2020, p. 10.

- ^ Toku 2004.

- ^ a b c d Suter 2013, p. 548.

- ^ a b Shamoon 2012, p. 104.

- ^ a b Orbaugh 2003, p. 114.

- ^ a b Welker 2015, p. 48.

- ^ a b Shamoon 2012, p. 105.

- ^ Welker 2015, p. 49.

- ^ a b c Welker 2015, p. 50.

- ^ a b Welker 2015, p. 52.

- ^ a b c Ogi 2008, p. 152.

- ^ a b c Ogi 2008, p. 157.

- ^ a b c Ogi 2008, p. 153.

- ^ a b Ogi 2008, p. 154.

- ^ a b c Choi 2015.

- ^ a b Ogi 2008, p. 160.

- ^ a b "The godmother of manga sex in Japan". BBC. March xvi, 2016. Archived from the original on January 29, 2022. Retrieved Feb 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c Ogi 2008, p. 161.

- ^ a b Shamoon 2012, p. 111.

- ^ a b c Ogi 2008, pp. 148–149.

- ^ "週刊少女コミック 1976年" [Weekly Shōjo Comic, 1976]. Shiryoukan (in Japanese). Archived from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Suzuki 1999, p. 251.

- ^ Ogi 2008, p. 162.

- ^ Brient 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "風と木の詩" [Kaze to Ki no Uta]. Mangapedia (in Japanese). Heibonsha, Shogakukan, et al. Archived from the original on February 9, 2022. Retrieved February sixteen, 2022.

- ^ "Milky Style Ediciones licencia Kaze to Ki no Uta, Tongari bôshi no atelier y Tetsugaku Letra" [Milky Manner Ediciones licenses Kaze to Ki no Uta, Tongari bôshi no atelier and Tetsugaku Letra]. Listado Manga (in Spanish). May 22, 2018. Archived from the original on Baronial 4, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c Mizoguchi 2003, p. 53.

- ^ Welker 2006, p. 855.

- ^ Welker 2006, p. 843.

- ^ Welker 2006, p. 856.

- ^ a b Fujimoto 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Fujimoto 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Fujimoto 2004, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b Fujimoto 2004, p. 85.

- ^ Nagaike & Aoyama 2015, p. 121.

- ^ Fujimoto 2004, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Fujimoto 2004, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Matsui 1993, p. 185.

- ^ a b Matsui 1993, p. 186.

- ^ Suzuki 1999, pp. 257–258.

- ^ Suzuki 1999, p. 258.

- ^ Suter 2013, p. 551.

- ^ Ogi 2008, p. 155.

- ^ Ogi 2008, p. 156.

- ^ a b Suter 2013, p. 552.

- ^ Welker 2015, pp. 49–50.

- ^ "小学館漫画賞:歴代受賞者" [Shogakukan Manga Award: Past Winners]. Shogakukan. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved February sixteen, 2022.

- ^ "歴代少女マンガ 発行部数ランキング" [Shoujo Manga All-Fourth dimension Circulation Ranking]. Nendai-ryuukou.com (in Japanese). Archived from the original on Dec twenty, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Toku 2007, p. 27.

- ^ Welker 2015, p. 51.

- ^ a b c Matsui 1993, p. 188.

- ^ McLelland 2015, pp. 264, 266.

- ^ McLelland 2015, p. 266.

- ^ "特集 安彦良和インタビュ" [Interview with Yoshikazu Yasuhiko]. Comic Natalie (in Japanese). June 28, 2019. Archived from the original on February seven, 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ Welker 2006, p. 849.

- ^ Takemiya, Keiko (September one, 1995). "Introduction by Norie Masuyama". 風と木の詩 第10巻 [Kaze to Ki no Uta vol. 10]. Hakusensha . ISBN978-4592881605.

Bibliography [edit]

- Azusa, Noah (2021). "The "Mystery" of Young Girls in Flower". Mechademia. 14 (1): 77–89.

- Brient, Hervé (Dec 2013). "Hagio Moto, une artiste au cœur du manga moderne". du9 (in French). Archived from the original on July xviii, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- Choi, Elise (2015). "Shōjo Aesthetics: Grade and Fantasy in Kaze To Ki No Uta" (Thesis). University of Oregon. Archived from the original on January 31, 2022. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- Fujimoto, Yukari (2004). Translated past Flores, Linda; Nagaike, Kazumi; Orbaugh, Sharalyn. "Transgender: Female Hermaphrodites and Male Androgynes". U.S.-Japan Women'due south Journal (27): 76–117. Archived from the original on 2022-02-ten. Retrieved 2022-02-17 .

- Hemmann, Kathryn (2020). Manga Cultures and the Female Gaze. London: Springer Nature. ISBN978-three-030-18095-9. Archived from the original on Apr 13, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- McLelland, Mark; Nagaike, Kazumi; Katsuhiko, Suganuma; Welker, James, eds. (2015). Boys Dearest Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Customs in Nihon. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN978-1628461190.

-

- McLelland, Mark (2015). "Regulation of Manga Content in Japan: What Is The Future for BL?". Boys Love Manga and Beyond. pp. 253–273. doi:x.14325/mississippi/9781628461190.003.0003. ISBN9781628461190.

- Nagaike, Kazumi; Aoyama, Tomoko (2015). "What is Japanese 'BL studies?': A historical and analytical overview". Boys Love Manga and Beyond. pp. 119–140.

- Welker, James (2015). "A Cursory History of Shōnen'ai, Yaoi and Boys Love". Boys Love Manga and Beyond: 42–75. doi:ten.14325/mississippi/9781628461190.003.0003. ISBN9781628461190.

- Matsui, Midori (1993). "Niggling Girls Were Petty Boys: Displaced Femininity in the Representation of Homosexuality in Japanese Girls' Comics". In Gunew, Sneja; Yeatman, Anna (eds.). Feminism and The Politics of Difference. Allen & Unwin. pp. 177–196. ISBN978-1863735087.

- Mizoguchi, Akiko (2003). "Male-Male Romance past and for Women in Japan: A History and the Subgenres of Yaoi Fiction". U.Due south.-Japan Women's Journal (25): 49–75. Archived from the original on 2022-02-10. Retrieved 2022-02-17 .

- Nagaike, Kazumi (2003). "Perverse Sexualities, Perversive Desires: Representations of Female Fantasies and "Yaoi Manga" every bit Pornography Directed at Women". U.Southward.-Japan Women'due south Periodical (25): 76–103. Archived from the original on 2022-02-x. Retrieved 2022-02-17 .

- Ogi, Fusami (2008). "Shôjo Manga (Japanese Comics for Girls) in the 1970s' Japan equally a Message to Women'due south Bodies: Interviewing Keiko Takemiya – A Leading Creative person of the Year 24 Blossom Group". International Journal of Comic Fine art. 10 (2): 148–169. ISSN 1531-6793.

- Orbaugh, Sharalyn (2003). "Inventiveness and Constraint in Amateur Manga Production". U.S.-Nihon Women's Journal (25): 104–124. Archived from the original on 2022-02-10. Retrieved 2022-02-17 .

- Shamoon, Deborah (2012). "The Revolution in 1970s Shōjo Manga". Passionate Friendship: The Aesthetics of Daughter's Civilisation in Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN978-0-82483-542-2.

- Suter, Rebecca (2013). "Gender Bending and Exoticism in Japanese Girls' Comics". Asian Studies Review. 37 (4): 546–558. doi:10.1080/10357823.2013.832111.

- Suzuki, Kazuko (1999). Inness, Sherrie (ed.). "Pornography or Therapy? Japanese Girls Creating the Yaoi Phenomenon". Millennium Girls: Today's Girls Around the World. London: Rowman & Littlefield: 243–267. ISBN0-8476-9136-5.

- Thorn, Rachel (2010). "The Magnificent 40-Niners". A Drunken Dream and Other Stories. Fantagraphics Books. pp. Five–VII. ISBN978-i-60699-377-4.

- Toku, Masami (2004). "The Power of Girls' Comics: The Value and Contribution to Visual Culture and Society". Visual Culture Research in Art and Didactics. Chico: California Country University, Chico. Archived from the original on October 14, 2018. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- Toku, Masami (2007). "Shojo Manga! Girls' Comics! A Mirror of Girls' Dreams". Mechademia. 2: 19–32. Archived from the original on 2022-02-10. Retrieved 2022-02-17 .

- Welker, James (2006). "Beautiful, Borrowed, and Bent: 'Boys' Love' every bit Girls' Love in Shôjo Manga'". Signs: Journal of Women in Civilization and Guild. 31 (3): 842. doi:10.1086/498987. S2CID 144888475.

External links [edit]

- Kaze to Ki no Uta (manga) at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- Kaze to Ki no Uta: Sanctus (OVA) at Anime News Network'south encyclopedia

- Kaze to Ki no Uta: Sanctus at IMDb

Kaze to Ki No Uta Read Online Volume 12

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaze_to_Ki_no_Uta

0 Response to "Kaze to Ki No Uta Read Online Volume 12"

Post a Comment